Interview Question: Why Do We Need Interfaces in Golang?

Introduction

Imagine you’re building a zoo app in Golang where animals like dogs, cats, and llamas need to make sounds and move around. You could write separate functions for each animal, but that’d get messy fast. Enter Golang interfaces—a simple yet powerful tool that lets you handle different types with one neat solution. As a software engineer, I’ve seen this question pop up in interviews: “Why do we need interfaces in Golang when we can just define functions?” Let’s break it down in a way that’s easy to grasp, exploring the interface in Go, its benefits, and why it’s a game-changer.

What Are Interfaces in Golang?

In Golang, an interface definition in Go is a type that lists method signatures—no fields, no implementation, just a blueprint of behaviors. For example:

type Animal interface {

Sound() string

Move() string

}

Any type that defines these methods—like Dog or Cat—automatically implements the interface. This implicit interface implementation is unique to Go and keeps things straightforward, unlike languages where you’d explicitly say implements. It’s all about structured typing in Go, where compatibility comes from matching methods, not declarations.

Why Use Interfaces When Functions Exist?

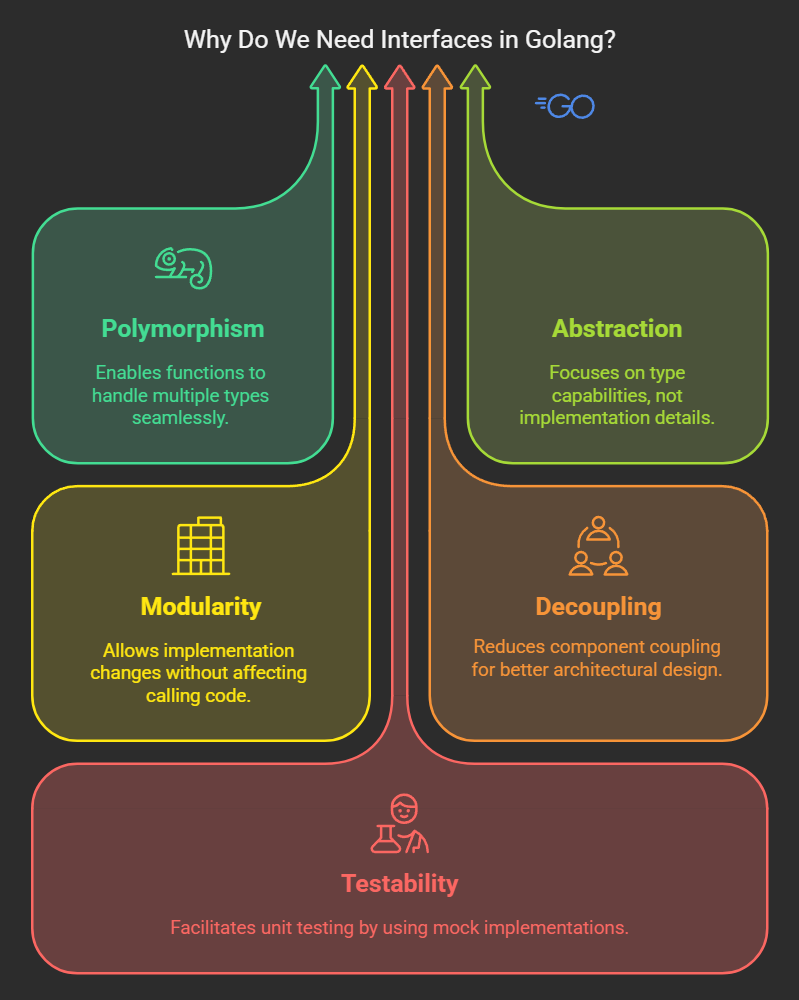

Sure, you can write a function like printDogSound(d Dog) without interfaces, but what if you add a Cat later? You’d need a new function, printCatSound(c Cat), repeating code and violating the DRY principle (Don’t Repeat Yourself). Interfaces solve this by letting one function handle multiple types. Here’s why we need them:

1. Polymorphism in Golang

Polymorphism in Golang means a single function can work with different types, as long as they implement the interface. Check this out:

type Dog struct{}

func (d Dog) Sound() string { return "Woof" }

func (d Dog) Move() string { return "Run" }

type Cat struct{}

func (c Cat) Sound() string { return "Meow" }

func (c Cat) Move() string { return "Walk" }

func Describe(a Animal) {

fmt.Println("Sound:", a.Sound(), "Move:", a.Move())

}

func main() {

d := Dog{}

c := Cat{}

Describe(d) // Sound: Woof Move: Run

Describe(c) // Sound: Meow Move: Walk

}

Without the Animal interface, you’d write separate DescribeDog and DescribeCat functions. Interfaces enable code reusability with interfaces, saving effort and keeping your codebase clean.

2. Interface Abstraction

Interfaces provide interface abstraction, focusing on what a type can do, not how it does it. In our zoo, Animal doesn’t care if Dog barks or Cat meows—it just needs a Sound(). This abstraction of behavior makes your code flexible and easier to extend, a key advantage I’ve seen in real projects.

3. Code Modularity in Go

By defining behavior in an interface, you can swap implementations without touching the calling code. Add a Llama tomorrow? Just implement Sound() and Move(), and Describe works fine. This code modularity in Go keeps your system scalable and maintainable.

4. Decoupling with Interfaces

Interfaces in Golang reduce tight coupling between components, which is a huge advantage for architectural decoupling. When a function depends on an interface like Animal, it doesn’t need to know the internal details of concrete types like Dog or Cat. This separation keeps your code flexible and easier to maintain, as changes to one part don’t ripple through the entire system. It also simplifies dependency management by reducing direct ties between structs and functions.

For example, let’s say you’re building a zoo management system. Without interfaces, a function might look like this, tightly coupled to Dog:

type Dog struct {

name string

}

func (d Dog) Sound() string {

return "Woof"

}

func PrintDogSound(d Dog) {

fmt.Println(d.Sound())

}

If you add a Cat, you’d need a new function, PrintCatSound, duplicating effort. With an Animal interface, you decouple the function from specific types:

type Animal interface {

Sound() string

}

type Dog struct {

name string

}

func (d Dog) Sound() string {

return "Woof"

}

type Cat struct {

name string

}

func (c Cat) Sound() string {

return "Meow"

}

func PrintSound(a Animal) {

fmt.Println(a.Sound())

}

func main() {

d := Dog{name: "Buddy"}

c := Cat{name: "Whiskers"}

PrintSound(d) // Output: Woof

PrintSound(c) // Output: Meow

}

Here, PrintSound only cares about the Animal interface, not Dog’s or Cat’s internals. This decoupling means you can add a Llama later without touching PrintSound.

Another perk? Import cycle resolution. In larger projects, circular imports can happen when two packages depend on each other. By defining an interface in a separate package, you break that cycle. Imagine:

package animalsdefinestype Animal interface { Sound() string }package dogimportsanimalsand implementsDogpackage printerimportsanimalsand usesAnimal, notDogdirectly

No circular imports, cleaner architecture—interfaces make it possible.

5. Testability with Mocks

Interfaces shine in unit testing by enabling testability with mocks. You can create a fake implementation of an interface to test your code without relying on real, complex types. This isolates the behavior you’re testing, making it easier to verify and debug.

Let’s expand our Animal example. Suppose you have a Zoo struct that uses an Animal:

type Animal interface {

Sound() string

Move() string

}

type Zoo struct {

resident Animal

}

func (z Zoo) Announce() string {

return "Hear: " + z.resident.Sound() + ", See: " + z.resident.Move()

}

To test Announce without real animals, create a MockAnimal:

type MockAnimal struct {

sound string

move string

}

func (m MockAnimal) Sound() string {

return m.sound

}

func (m MockAnimal) Move() string {

return m.move

}

func TestZooAnnounce(t *testing.T) {

mock := MockAnimal{sound: "Test", move: "Stand"}

zoo := Zoo{resident: mock}

result := zoo.Announce()

expected := "Hear: Test, See: Stand"

if result != expected {

t.Errorf("Expected %q, got %q", expected, result)

}

}

Here, MockAnimal lets you control the test input precisely. Want to test an edge case? Tweak the mock:

mockEdge := MockAnimal{sound: "", move: "Jump"}

zooEdge := Zoo{resident: mockEdge}

result := zooEdge.Announce() // "Hear: , See: Jump"

This testability with mocks is practical because:

- It avoids real implementations (e.g., a

Dogmight fetch data from a database). - It’s fast—no setup for complex types.

- It isolates

Zoo’s logic, ensuringAnnounceworks as expected.

In a real project, I’ve used this to mock database connections or APIs. For example, an AnimalFetcher interface could be mocked to return test data, keeping tests independent of live systems. Interfaces make this seamless, proving their worth beyond basic functions.

How Interfaces Fit Into Go’s Philosophy

Go favors composition vs inheritance, and interfaces play a starring role. Instead of inheriting behavior from a base class, you compose types with interfaces. A Dog doesn’t inherit from Animal—it just implements it. This keeps things simple and avoids the complexity of deep inheritance trees.

Then there’s the empty interface (interface{}), which has no methods, so every type implements it:

func PrintAnything(v interface{}) {

fmt.Println(v)

}

It’s handy for generic stuff, but use it wisely—more on that later.

Real-World Use Cases

Mocking for Unit Tests

As shown, interfaces let you mock dependencies, speeding up testing without real implementations.

Dependency Injection with Interfaces

Pass an interface to a function or struct instead of a concrete type:

type Zoo struct {

animal Animal

}

func NewZoo(a Animal) *Zoo {

return &Zoo{animal: a}

}

This dependency injection with interfaces keeps your code adaptable.

Abstraction of Behavior

In a payment system, a PaymentProcessor interface can abstract CreditCard or PayPal implementations, letting you switch processors without rewriting logic.

Architectural Decoupling

In large apps, interfaces separate layers (e.g., database vs. business logic), reducing dependencies and easing maintenance.

Import Cycle Resolution

Define an interface in a neutral package to break circular imports between types, a low-competition keyword worth noting for Go devs.

Best Practices for Interface Usage in Golang

Small Interfaces Design

Keep interfaces small, like io.Reader with one method (Read). This small interfaces design makes them easy to implement and reuse, as advised in Go’s philosophy.

Granular Interface Definitions

Break big interfaces into smaller ones. Instead of:

type BigInterface interface {

Read()

Write()

Close()

}

Use:

type Reader interface { Read() }

type Writer interface { Write() }

Composing Interfaces from Smaller Ones

Combine small interfaces for flexibility:

type ReadWriter interface {

Reader

Writer

}

This composing interfaces from smaller ones mirrors Go’s composition ethos.

Avoiding Overuse of Empty Interfaces

The empty interface (interface{}) is tempting but can hide type safety. Use it sparingly, preferring specific interfaces or generics (since Go 1.18) for clarity.

Why Not Just Functions?

Without interfaces, you’d:

- Repeat code for every type (no DRY principle).

- Lose flexibility to add new types easily.

- Couple functions to specific structs, complicating changes.

Interfaces bring interface usage in Golang to life, offering benefits and advantages like reusability, decoupling, and testability that plain functions can’t match alone.

Conclusion: The Power of Interfaces

Golang interfaces aren’t just a fancy feature—they’re a practical necessity for writing clean, scalable code. From polymorphism in Golang to decoupling with interfaces, they solve real problems I’ve tackled in projects. For students or devs new to Go, play with small examples like our Animal interface, then explore A Tour of Go for hands-on practice. Got questions? Drop them below—let’s chat about how interfaces can level up your Golang skills!